Position Article

Written by Fabiola Perales, Especialista de Mejora Regulatoria y Doctorante en Políticas Públicas | Twitter: @FabiolaOPerales

In Mexico, during 2020, the Regulatory Policy (also called Regulatory Improvement Policy or Better Regulation Policy) has been involved in a series of political pressures. These actions are questioning the functioning and public value of the National Commission for Regulatory Improvement (CONAMER, before COFEMER) and its regulatory review processes. These events have motivated me to write this brief article with the aim of contributing to the construction of the conceptualization, culture, and implementation of the better regulation policy as an academic discipline and as a public policy. This article is organised in three sections, the first one deals with the relevance of integrating the better regulation culture into the regulatory governance cycle with the aim of being located in a visible place and working on it, the second section addresses the case of regulatory policy in Mexico, and the third section presents some brief conclusions.

The relevance of the culture of better regulation into the regulatory governance cycle

In general, the Regulatory Policy establishes the rules of the game about how regulations are made, issued, applied, and evaluated; who can participate in those processes and under what terms. It is the public policy in charge of reviewing the regulatory framework (both the flow and the stock) through values, principles, and rules that foster interaction between government institutions and social and private sector actors, with the aim to convey the citizens and businesses concerns (possible failures, weaknesses, omissions or gaps in rules) about social and/or economic legal systems to the government bodies. This mechanism is intended to enrich and improve the content of the regulations.

The OECD (2011) has pointed out that Regulatory Policy aims to ensure that regulations are in the public interest, are justified, of good quality and “fit for purpose”, and boosted the coherence of public policies (p. 18). It also remarks that the “regulatory policy helps to shape the relationship between the state, citizens, and businesses” (p. 18). And has emphasized that “an effective regulatory policy supports economic development as well as the rule of law, helping policymakers to reach informed decisions about what to regulate, whom to regulate, and how to regulate” (p. 18).

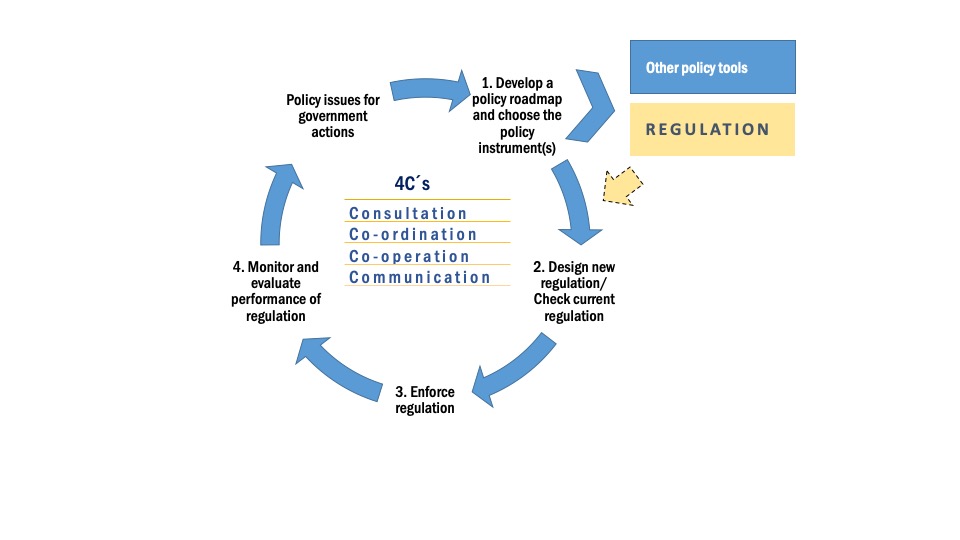

In order to promote the adoption of the Regulatory Policy, the OECD (2011) has proposed to analyse the issuance of regulations from “the regulatory governance cycle”. This cycle is similar to the cycle of public policies, and it should not be surprising because regulations are a type of public policy. Conceptualizing the cycle, the OECD (2011) integrates the term “regulatory governance”, which seeks to give a “practical effect to regulatory improvement policy” (p. 74). The regulatory governance cycle allows visualizing the coordination of regulatory measures “from the design and development of regulations, to their implementation and enforcement, closing the loop with monitoring and evaluation which informs the development of new regulations and the adjustment of existing regulations” (p. 74). For the OECD (2011), the image of the cycle seeks to stimulate both collective and individual country reflection on the functions and processes that must be fulfilled in order to ensure that government intervention options (regulatory or non-regulatory) are evaluated before they are adopted and that actors and institutions that assume those functions (or that should assume them) can participate (p. 74).

Para el desarrollo de este ciclo, la OCDE (2011) prevé la necesidad de cuatro componentes auxiliares, llamados “4´c”, estos son: consulta, coordinación, cooperación y comunicación.

For the development of this cycle, the OECD (2011) foresees the need for four auxiliary components, called the 4C’s, these are: consultation, co-ordination, co-operation, and communication.

- The “open and balanced” public consultation (OECD, 2012) aims to “inform the legitimate needs of those concerned by and affected” (p. 8) by government regulatory interventions. It can be conducted throughout the entire cycle (p. 8).

- The co-ordination of regulatory actions and the co-operation of regulatory agents are elements that allow the generation of coherence in the regulatory framework. They help to “avoid conflicts between different rules and promote legal certainty for the regulatee” (OECD, 2016, p. 20).

- Communicating the obligations, costs, and benefits of regulations is key to promote compliance (OECD, 2016, p. 20). Therefore, the implementation of communication strategies is necessary throughout the cycle.

These four components give life and dynamism to the regulation cycle and are critical to the improvement of regulatory instruments. However, none of the 4C’s ensures that a society can fully engage in this way of elaborating, analysing, and reflecting on regulations. To achieve a social commitment to this form of rethinking the regulatory process, it is necessary that society knows the values promoted by the regulatory policy, understand how the rules (inspired by the regulatory governance cycle) of the process of making and improving regulations work from the Better Regulatory approach, aware of what can be expected from these processes and what cannot, and participate in them.

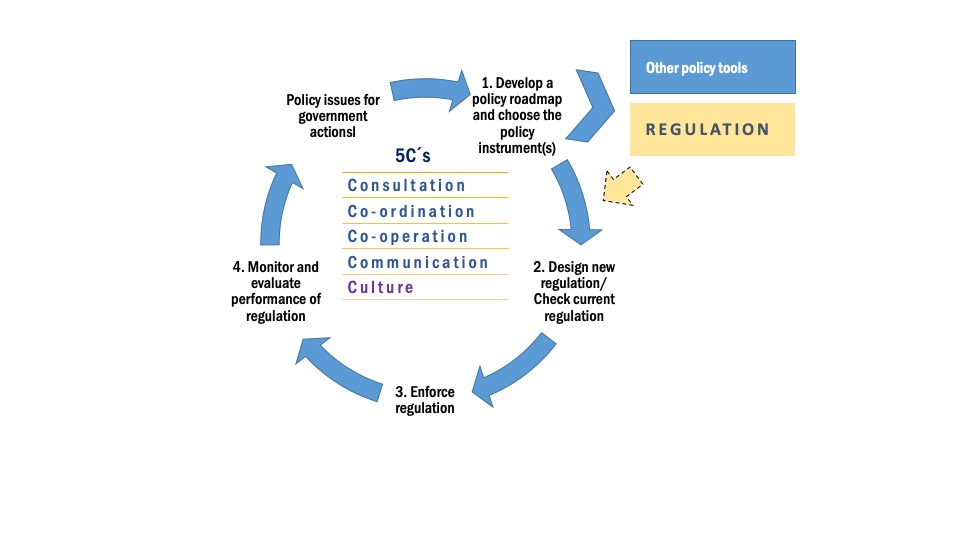

Given this, it would be important to include a fifth component to the regulatory governance cycle, the fifth “C”: the culture of better regulation. This component is difficult to create by simply implementing the Regulatory Policy, as the other 4C’s, it needs to be developed.

Culture is a complex set of “knowledge, belief, art, morals, law, custom, and any other capabilities and habits acquired by man as a member of society” (Tylor, 1871). In other words, culture is “a learned set of traditions and lifestyles, socially acquired, of the members of society, including their standardized and repetitive ways of thinking, feeling and acting (i.e., their behaviour)” (Harris et al, 1990, p. 4). Culture “involves both a shared system of responses and a social design of individual behaviour” (Marín, 1997, p. 68). In this way, “we can speak of culture from the moment that human interaction generates tacit consensus or patterns of thought and action that are adopted by different members of the organization without formal decisions or rules” (López & Sánchez, 2004, p. 8).

Therefore, to ensure that the better regulation approach is adopted in the processes of issuing and reviewing regulations, it is necessary to promote, develop and defend its knowledge, values, principles, and rules, both within and outside of public organizations. Also, to facilitate in a society the creation of cultural features (such as behaviours, beliefs or ideas) on Better Regulation, it would be important that these cultural features: (1) be shared socially, (2) be transmitted in order to become durable, and (3) be learned (Marín, 1997, p. 68). That is because the “culture is not initially possessed in an innate way, but rather, it is received through interaction and a process of socialization by others who possess it” (p. 69).

In this regard, I propose that the regulatory governance cycle should consider the need and importance of developing and promoting a culture of better regulation throughout government and in society at large.

Figure 2. Regulatory Governance Cycle, including 5’c

Source: OECD, 2011, p. 76, modified.

A culture of better regulation adopted by a country’s public administration and society would imply:

- Recognize public value generated by the adoption and implementation of Regulatory Policy. It “must be able to show that the results obtained are worth the cost of private consumption and unrestrained liberty forgone in producing the desirable results” (Moore, 1995, p. 29). This can be observed from two perspectives, the first one, from each regulation when the benefits exceed the costs it imposes, and the second one, when the costs of the interaction of companies and citizens (time, resources and effort) with the government during the process of drafting, reviewing, monitoring and evaluating regulations are worth by the benefits generated by the regulatory improvement process itself. These benefits could be translated into having quality, efficient, and intelligent regulatory frameworks that represent the public interest and strengthen the State of law.

- Prioritize in the elaboration and review of regulations, the values of transparency, public consultation, public dialogue, public interest, technical cooperation, coherence between policies, administrative simplification, continuous improvement, effectiveness and efficiency of regulations, evaluation and accountability, and citizen protest against excessive, onerous, and unnecessary rules.

- Establish as basic principles of regulatory policy, at least the following ones: “regulations should generate benefits greater than costs and maximum benefit to society”, and “regulatory improvement process should operate under the principle of maximum publicity unless it is proven that advance publicity of the project compromises the effects of regulation”.

- Avoid actions such as regulatory capture, simulation in the application of the rules of the game of regulatory policy, opacity in regulatory review processes, acts of corruption such as bribery in the application of regulations, and the omission of actions or negligence in the process of improvement or in the process of application of regulations, mainly.

- Place citizens at the centre of public decision-making.

- Promote and teach from the classrooms the understanding of the values, principles, and rules of better regulation.

- Understand that regulatory improvement is not only a task of the public body in charge of it but also it is a task for society as a whole, in order to maintain it and promote it as an academic discipline and as a public policy, in order to reconfigure the way of thinking, drafting and applying regulations.

- Exercise the values, principles, and rules of regulatory improvement at all levels of government and in all State bodies.

Without the emphasis on developing and fostering a culture of better regulation, the efforts of countries that decide to adopt this Policy could be limited and could be counteracted by the prevailing culture. If the rules of the regulatory improvement game are not known or understood, it is difficult for society to enforce them in the courts, hence the importance of including the fifth C in the regulatory governance cycle.

The case of Regulatory Policy in Mexico

This is not the first time that CONAMER has been under political pressure, and it may not be the last either. In 2010, the Commission had to renew itself in order to avoid the (more credible) threat of being disappeared. The transformation of the Commission in 2010 came from inside because it was perfectly understood why it was important to keep the Commission and the policy active in Mexico.

In the period from 2010 to 2012, the face of the Commission changed. Based on the international experience, taking as a reference the recommendations from the OECD and the work carried out by Australia, New Zealand, United Kingdom, Netherlands, and Canada, multiple actions were undertaken and made concrete that today are an international reference. Some outstanding ones were:

(1) The regulatory impact calculator was developed, which allowed to stablish a differentiated review process, thus creating the high-impact RIA and the moderate-impact RIA;

(2) The Regulatory Impact Assessment Manual (still in force) was formally issued in the Federal Official Gazette. This Manual regulates every detail of the regulatory improvement process;

(3) Regulatory competition and risk analyses were integrated into the RIA system;

(4) Ex-post RIA was created;

(5) a Common Regulatory Improvement Agenda was proposed for the first time to promote all the regulatory improvement tools in the States and not only the one-stop shops;

(6) with the methodology of the Indicators of Regulatory Management System of the OECD (2009), a Regulatory Improvement Indicator was created for the first time for the State governments, which today is the basis of the Sub-national Regulatory Improvement Indicator of the corresponding National Observatory;

(7) The project to measure administrative burdens was initiated, taking as a reference the Standard Cost Model (SCM) created in the Netherlands, and the first measurement of administrative burdens at the federal level was achieved;

(8) Technical cooperation work was initiated with Latin American countries; and

(9) Training of the Commission’s public servants and citizens was promoted through the development of the Diploma courses on regulation, which were online, free and open-access.

None of these actions were easy, but all of us who were at the scene at that particular moment did understand the message: we were called upon to transform the regulatory improvement system in Mexico and to place it in a less vulnerable position than it was. The option chosen was to provide public value to the Commission’s work as well as to show signs of fulfilling its mandate of “ensuring that regulations generate benefits that outweigh costs and maximize benefits for society”. Legal reforms for the strength of the system had to wait.

Thus, the 2020 CONAMER is not the same as the 2010 COFEMER. Today, the Regulatory Policy has constitutional status. Many of the rules of the process were set out in the General Law that was issued in 2018. The highest governing body of the policy is the National Council, integrated by Governors, Presidents of National Business Chambers, Secretaries of State and Civil Society Associations. CONAMER also has an auxiliary body, the National Better Regulation Observatory, in which its members have the legal and moral obligation to call to order and harmony when the review processes deviate from the rule-of-law.

Today, Mexican society understands and has come to know the public value generated by CONAMER: quality and simpler regulations and transparent review processes. Therefore, the protection of the values, principles, and rules of regulatory policy could come in this 2020 from the society, as well as political actors involved in the National System of Regulatory Policy.

A system with 31 years of work like the one we have built-in Mexico allows us to judicialize the regulatory measures that contravene the values, principles, and rules of regulatory policy. This means that those interested in or affected by poorly conducted regulatory improvement processes can assert their rights in the courts. On the other hand, our system includes Better regulation Chapters in commercial treaties. The Pacific Alliance in its chapter 15 Bis and the Free Trade Agreement between the United States, Mexico, and Canada (T-MEC) in its chapter 28 address the “Best Regulatory Practices” that the signatory countries commit to comply with. These international cooperation mechanisms reinforce and guarantee which the Mexican State must comply with and enforce.

The events between the Commission and the energy sector in 2020, make it possible and credible that the public servants of CONAMER do not have today the possibility to promote in its maximum expression as in 2010 the public value that the Commission is obliged to give. However, the institutional framework that today shapes the regulatory policy would allow civil society, private sector and judicial branch could be guarantor bodies of the values, principles, and rules of better regulation. This circumstance could be an opportunity to “democratize the policy” and accelerate the collective learning processes of better regulation at all levels and sectors of society so that individuals and companies can demand the compliance of rules of the game in drafting and reviewing of regulations, and also thus strengthen the culture of better regulation.

Conclusion

Because of the multiple interests and perspectives involved in implementing the regulatory policy, regulatory oversight bodies (such as CONAMER in Mexico, the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (OIRA) in the United States, the Office of Best Practice Regulation (OBPR) in Australia or the Organism for Better Regulation (OMR) in El Salvador) in charge of it may constantly face internal and external political pressure. The nature of these bodies is to be mediators between regulatory bodies and citizens and businesses. One way to strengthen the application of the values, principles, and rules of regulatory policy is to develop a culture of better regulation both at the organizational level in the public sector and at the level of society, in all economic and social sectors.

Including the culture of better regulation in the regulatory governance cycle would allow countries to emphasize both the development of regulatory policy rules and to seek to influence the way (habits, customs, and social rules) in which regulations are thought and applied at the societal level.

As a result of its political context, today Mexico has the opportunity to continue developing the regulatory policy by promoting the culture of better regulation from civil society, the private sector, and the judicial branch. Coordinating actions to make comply the Mexican Government and local governments with the rules of this policy, would help to consolidate the system and increase the culture itself.

On the other hand, a pending subject in Mexico is the promotion of the culture of better regulation from universities and research centres. In order to continue advancing in the development of policy and the theorization of better regulation as a discipline, it would be important for universities to include in their study programs, subjects related to regulatory policy tools, or specific topics that address the issue. Likewise, they could develop university extension programs such as diploma courses or courses in which the skills and capacities of professionals from the government and the private and social sectors could be further developed. They could also develop university extension programmes, such as diploma courses or courses, in which the skills and capacities of professionals from the government and the private and social sectors can be further developed. Research centres could incorporate into their priorities a theoretical view of regulatory policy and insert themselves into the debates already taking place at the international level.

Finally, for those Latin American and Caribbean countries that are beginning to build their regulatory improvement system, it would be worthwhile to suggest that along with policy design and implementation, they can focus on seeking and promoting a cultural change towards better regulation.

If you want to know your level of better regulation culture, click here and answer six short questions: https://es.surveymonkey.com/r/FYCHWKR

References

Harris, M., Bordoy, V., Revuelta, F., & Velasco, H. M. (1990). Antropología cultural. Madrid: Alianza editorial.

López J., & Sánchez, M. R. (2004). La cultura institucional. Organización y gestión de centros educativos.

Marín, L. (1997). La comunicación en la empresa y en las organizaciones. Bosch Casa Editorial, Barcelona España.

Moore, M. H. (1995). Creating public value: Strategic management in government. Harvard university press.

OECD (2009). Indicators of regulatory management systems, 2009 Report. OECD Publishing. https://www.oecd.org/gov/regulatory-policy/44294427.pdf

OECD (2011), Regulatory Policy and Governance: Supporting Economic Growth and Serving the Public Interest, OECD Publishing. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264116573-en

OECD (2012), Recomendación del Consejo sobre Política y Gobernanza Regulatoria, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264209046-es.

OECD (2016), El abc de la mejora regulatoria para las entidades federativas y los municipios: Guía práctica para funcionarios, empresarios y ciudadanos. OECD Publishing. http://www.oecd.org/regreform/regulatory-policy/mexico.htm

Tylor, E. B. (1871). Primitive culture; Part 1: The origins of culture. London: Murray.

Notes:

[1] Revised on August 2, 2020, in the link: https://encyclopaedia.herdereditorial.com/wiki/Rasgo_cultural

Cite this publication:

Perales-Fernández, F. (2020). The Better Regulation Culture. Blog de Mejores Gobiernos. www.mejoresgobiernos.org